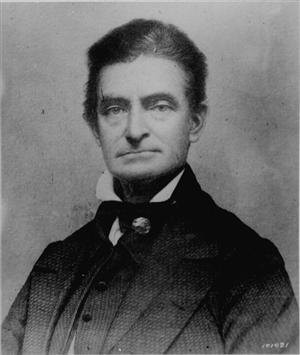

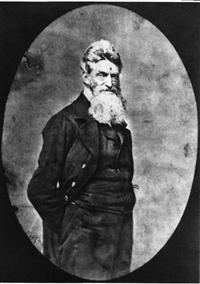

John Brown

(May 9, 1800 – December 2, 1859)

(May 9, 1800 – December 2, 1859)

John Brown was an American abolitionist, and folk hero who advocated and practiced armed insurrection as a means to end all slavery. He led the Pottawatomie Massacre in 1856 in Bleeding Kansas and made his name in the unsuccessful raid at Harpers Ferry in 1859.

Early Years

John Brown was born May 9, 1800, in Torrington, Connecticut. He was the fourth of the eight children of Owen Brown and Ruth Mills. In 1805, the family moved to Hudson, Ohio, where Owen Brown opened a tannery.

At the age of 16, John Brown left his family and went to Plainfield, Massachusetts, where he enrolled in a preparatory program. Shortly afterward, he transferred to the Morris Academy in Litchfield, Connecticut.[8] He hoped to become a Congregationalist minister, but money ran out and he suffered from eye inflammations, which forced him to give up the academy and return to Ohio. In Hudson, he worked briefly at his father's tannery before opening a successful tannery of his own outside of town with his adopted brother.

In 1820, Brown married Dianthe Lusk. Their first child, John Jr, was born 13 months later. In 1825, Brown and his family moved to New Richmond, Pennsylvania, where he bought 200 acres (81 hectares) of land. He cleared an eighth of it and built a cabin, a barn, and a tannery. Within a year the tannery employed 15 men. In 1831, one of his sons died. Brown fell ill, and his businesses began to suffer, which left him in terrible debt. In the summer of 1832, shortly after the death of a newborn son, his wife Dianthe died. On June 14, 1833, Brown married 16-year-old Mary Ann Day (April 15, 1817—May 1, 1884), originally of Meadville, Pennsylvania. They eventually had 13 children, in addition to the seven children from his previous marriage.

In 1836, Brown moved his family to Ohio near present day Kent. There he borrowed money to buy land in the area, building and operating a tannery along the Cuyahoga River. John Brown would suffer great financial losses during the economic crisis of 1839. Brown was declared bankrupt by a federal court on September 28, 1842. In 1843, four of his children died of dysentery. During the 1840s Brown entered into a partnership with Simon Perkins Jr of Akron, Ohio to raise sheep. The partnership prospered and expanded its business to Springfield, Massachusetts. But Brown made a risky decision that would cost the partnership tens of thousands of dollars. Perkins and Brown would eventually end their partnership in 1854, but would remain friends over the next five years.

In 1848, Brown heard of Gerrit Smith's Adirondack land grants to poor black men, and decided to move his family among the new settlers. He bought land near North Elba, New York (near Lake Placid), for $1 an acre, although he spent little time there. After he was executed, his wife took his body there for burial. Since 1895, the farm has been owned by New York state. The John Brown Farm and Gravesite is now a National Historic Landmark.

The Kansas Years

As early as 1837, John Brown began to make public his abolitionist feelings. In response to the murder of the abolitionist, Elijah P. Lovejoy, Brown publicly vowed: “Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery!”

Five of Brown's adult sons, including John Brown, Jr., had emigrated to the Kansas Territory in 1854, In 1855, his sons reported to Brown that pro-slavery forces there were militant and that they needed assistance to guard against any attack. John Brown did not hesitate and left for Kansas. He arrived at his sons farm near Osawatomie, Kansas on October 6, 1855. One week after arriving in Kansas, John Brown wrote about the political situation in Kansas to his wife, Mary:

“Last Tuesday was an Election day with Free State men in Kansas, & hearing that there a prospect of difficulty we all turned out most thoroughly armed ( except Jason who was too feeble ) but no enemy appeared; nor have I heard of any disturbance in any part of the Territory. Indeed I believe Missouri is fast becoming discouraged about making Kansas a Slave State, & think the prospect of its becoming Free is brightening every day.”

It's hard to understand why Brown was so optimistic. A pro-slavery territorial legislature had been elected in March 1855. Free staters felt there had been widespread election fraud as thousands of Missourians had crossed the border to vote on election day. In Washington, the Buchanan Administration had validated the election results and the territorial legislature was preparing to draft what would be known as the pro-slavery, Lecompton Constitution. Maybe Brown was merely trying to reassure his wife.

Later that year Douglas County Sheriff Samuel J. Jones led a pro-slavery militia force comprised mostly of Missourians against Lawrence, Kansas. In what would become known as the Wakarusa War, the Browns had come from Osawatomie to Lawrence's aid. Although the affair was settled peacefully through extended negotiations, John Brown must have begun to realize that the pro-slavery faction was not going to leave Kansas any time soon.

The Pottawatomie Massacre

In May 1856, the US District Court in Lecompton, Kansas had issued indictments against several free-state leaders. Once again Sheriff Jones had a posse headed for Lawrence. The Browns heard that Lawrence, Kansas was being threatened again. In response, John Brown, Jr. mobilized his free-state militia company, the Pottawatomie Rifles, and headed north to Lawrence. His father, “old” John Brown, accompanied them on their way to Lawrence. Before they reached Lawrence, the party discovered that they were too late and Lawrence had already been sacked. Old John Brown, some of his sons, and a few others went off by themselves as Captain John Brown, Jr. took the Pottawatomie Rifles back to Osawatomie.

In May 1856, the US District Court in Lecompton, Kansas had issued indictments against several free-state leaders. Once again Sheriff Jones had a posse headed for Lawrence. The Browns heard that Lawrence, Kansas was being threatened again. In response, John Brown, Jr. mobilized his free-state militia company, the Pottawatomie Rifles, and headed north to Lawrence. His father, “old” John Brown, accompanied them on their way to Lawrence. Before they reached Lawrence, the party discovered that they were too late and Lawrence had already been sacked. Old John Brown, some of his sons, and a few others went off by themselves as Captain John Brown, Jr. took the Pottawatomie Rifles back to Osawatomie.

John Brown must have been becoming increasingly frustrated by the lack of action against pro-slavery supporters. After they separated from the Pottawatomie Rifle company, John Brown would lead his small band to the homes of some settlers on Pottawatomie Creek a little west of Osawatomie, Kansas. They called themselves the Northern Army and late at night on May 24th, they stopped at the house of James P. Doyle. They forced their way into the house and took Doyle and two of his sons, William and Drury, prisoner. Outside of the house, the group of men led by John Brown killed the three Doyles, shooting them and hacking them with large knives. Their mutilated bodies were discovered the next morning. The free staters next went to the house of Allen Wilkinson where they forced their way into his house and took him prisoner. His dead body was found later that day. They continued on to the house of James Harris. They said they were looking for Henry Sherman. Although Henry Sherman was not present, his brother, William, was there.  The Northern Army took William Sherman prisoner and left. William Sherman's dead body was discovered during the day.

The Northern Army took William Sherman prisoner and left. William Sherman's dead body was discovered during the day.

Later the elder John Brown was quoted as saying, “I did not [commit the murders]; but I do not pretend to say that they were not killed by my order, and in doing so I believe I was doing God's service.” Charles Robinson spoke out against the violence, believing it would give the federal authorities justification for using force in their suppression of the free state movement. The violence in Kansas would now escalate.

The Battle of Black Jack

With Charles Robinson in jail in Lecompton, the more radical free state leaders, such as James H. Lane and John Brown, now exhorted their followers to take up arms against pro-slavery forces.

With Charles Robinson in jail in Lecompton, the more radical free state leaders, such as James H. Lane and John Brown, now exhorted their followers to take up arms against pro-slavery forces.

In response to the Pottawatomie Massacre, U.S. Deputy Marshal Henry C. Pate arrested John Brown, Jr. and his brother Jason Brown, turning them over to federal authorities. Early in June of 1856, Pate, in command of around 75 territorial pro-slavery militia, was encamped near Black Jack, Kansas. Early on the morning of June 2nd, two groups of free state men attacked Pate and his militia. John Brown led a group of about ten men while a Captain Samuel T. Shore led a group of 25 free state men.  The fighting lasted around 2 to 3 hours. Captain Shore and a significant number of the free state militia had retired and Brown was down to less than 20 men. John Brown's son, Frederick, rode around to the far side of Pate and yelled for them to surrender. Although Pate's militia outnumbered Brown and his men, Pate was fooled into thinking he was surrounded. Pate would surrender himself and 28 of his men. Brown would hold the prisoners hostage and later exchange them for his sons.

The fighting lasted around 2 to 3 hours. Captain Shore and a significant number of the free state militia had retired and Brown was down to less than 20 men. John Brown's son, Frederick, rode around to the far side of Pate and yelled for them to surrender. Although Pate's militia outnumbered Brown and his men, Pate was fooled into thinking he was surrounded. Pate would surrender himself and 28 of his men. Brown would hold the prisoners hostage and later exchange them for his sons.

The Battle of Osawatomie

Following a lot of guerrilla fighting during July and August, a force of 300 - 400 pro-slavery guerrillas under the command of John W. Reid approached Osawatomie, Kansas in late August looking for John Brown. Brown and his group of free state militia had just returned to Osawatomie the day before. Although exhausted from their trip, Brown prepared for a fight. They had been warned of the pro-slavery forces by a twelve-year-old boy named Charles Adair. Adair told Brown that the pro-slavery men had come upon Brown's son Frederick and killed him.

On the morning of August 30th, free state forces under the command of John Brown and J B. Cline established a line of defense in and around a log house just south of the Marais des Cygnes River. Although outnumbered, the free state forces were able to hold off Reid's pro-slavery forces for a short while until their ammunition ran low. The free state forces withdrew to the north side of the river and prepared another defensive line.

But the pro-slavery men did not follow them across the river. Instead they chose to set fire to the town of Osawatomie. Although John Brown and his band of free staters had been beaten in this fighting near his family's home in Osawatomie, Kansas, he began to become known nationally in his struggle against slavery.

One week after the fighting, John Brown wrote about the experience to his wife, Mary:

“On the morning of the 30th Aug an attack was made by the ruffians on Osawatomie numbering some 400 by whose scouts our dear Fredk was shot dead without warning he supposing them to be Free State men or near as we can learn. One other man a Cousin of Mr. Adair was murdered by them about the same time. At this time I was about 3 miles off where I had some 14 or 15 men over night that I had just enlisted to serve under me as regulars. There I collected as well as I could with some 12 or 15 more & in about ¾ of an Hour attacked them from a wood with thick undergroth, with this force we threw them into confusion for about 15 or 20 minutes during which time we killed & wounded from 70 to 80 of the enemy as they say & then we escaped as well as we could with one killed while escaping; two or three wounded; & as many more missing. Four or Five Free State men were butchered during the day as well. Jason fought bravely by my side during the fight & escaped with me he unhurt. I was struck by a partly spent Grape Canister, or Rifle shot which bruised me some but did not injure me seriously. “Hitherto the Lord both helped me” notwithstanding my afflictions. Things now seem rather quiet just now; but what another Hour will bring I cannot say...”

Brown Leaves Kansas

On July 31, 1856, President Franklin Pierce would appoint John W. Geary as the new governor of the Kansas Territory. In an attempt to stem the violence, Geary issued an order that all Kansas militia forces be disbanded. He planned to rely on the US Army to enforce the territorial laws. These actions would stem the violence to a certain degree. Near the end of 1856, Brown would take advantage of this truce and return to New England to raise money for the cause. Once again, Amos Lawrence would make a substantial contribution of money to the fight against slavery. Many other prominent abolitionists would contribute funds to assist Brown's antislavery work. Much of this money would be used to finance Brown's raid on the arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Virginia.

The Battle of the Spurs

In June of 1858, John Brown's plans to foment a slave revolution in the south had been put temporarily on hold. Brown decided to return to Kansas until events had calmed down back east. In December of 1858, John Brown led a band of twenty men in a raid across the border into Vernon County, Missouri. On December 21, 1858 Brown crossed the border back into Kansas with 11 fugitive slaves liberated from their slave owners in Missouri. They would begin a slow 2 ½ month journey of over 1,100 miles to their freedom.

The path Brown used followed The Lane Trail that Jame H. Lane had established in 1856 to enable free-state immigrants to avoid the roadblocks established by pro-slavery Missourians. Early in the morning of January 28th, they had to stop for awhile at Fuller's Station on Straight Creek north of Holton, Kansas. Here was where Aaron Stevens encountered a group of eight federal troops that were on the lookout for John Brown and the fugitive slaves. Stevens led the federals back to Fuller's Cabin. Once in the cabin, Stevens grabbed a Sharps rifle and turned it on the federals. One of the federals was captured while the other seven quickly rode away.

The path Brown used followed The Lane Trail that Jame H. Lane had established in 1856 to enable free-state immigrants to avoid the roadblocks established by pro-slavery Missourians. Early in the morning of January 28th, they had to stop for awhile at Fuller's Station on Straight Creek north of Holton, Kansas. Here was where Aaron Stevens encountered a group of eight federal troops that were on the lookout for John Brown and the fugitive slaves. Stevens led the federals back to Fuller's Cabin. Once in the cabin, Stevens grabbed a Sharps rifle and turned it on the federals. One of the federals was captured while the other seven quickly rode away.

Now Brown sent word back to Topeka for them to send him some reinforcements to help against the federals. The federals were part of a posse led by Deputy Marshall John P. Wood, who was operating out of Lecompton, Kansas. Now that Wood knew Brown was in the vicinity, he sent word back to Atchinson, Kansas for reinforcements of his own. By January 31st, John Brown's force had grown to 21 men and Wood's posse had grown to 45 men.

John Brown moved the fugitives up to Smith's Station on Spring Creek in the early morning of January 31, 1859. Wood's posse established their position on the north side of Spring Creek. Throwing caution to the wind, Brown ordered his men to cross the creek as rapidly as possible and charge the federals. Probably due to John Brown's reputation for fearlessness and violence, the federals withdrew as quickly as possible. There were no shots fired during this engagement. A reporter later called this The Battle of the Spurs, because the federals had used their horses to run away from the scene.

William F. Creitz, a resident of Holton who had served under Aaron Stevens, later described “the particulars of 'Old John Brown's' final departure from this territory”:

“The enemy's scouts kept hovering around Brown's position day and night, but were careful never to come within Sharps rifle range. At 10, o'clock A.M. of the 31 st of Jan the Topeka Company arrived in Brown's Camp: immediately preparations were made to commence the march. At 2 O'clock P.M. Straight Creek was safely crossed. and the entire party, fugitives included, numbering twenty- five men, were ordered to march directly for the headquarters of the ruffians, at Eureka.

As soon as the enemy became aware of Brown's approach. they beat to arms, and drew up their men in battle array, on an elevated position, in the rear of Eureka: their Scouting parties were called in, and the movements of both parties for some time indicated, that a general engagement was about to take place.

...The ruffians were all clamorous to be led into the fight, but when Brown's party had approached within rifle range, a sudden panic seized all; all fled precipitously down a steep hill to the spring creek crossing. At the latter point they felt assured of arresting Brown's further progress, until the arrival of the troops, who were now hourly expected. Sixty-five ruffians, the off scourings of the South, were drawn up in order of battle, on the north side of Spring creek; glorious deed they were expected to perform, immortality was to be their boon; This day was to witness the capture of Brown: his abolition was to be annihilated, and the the blood stained banner of the slave hunter wave in triumph over the virgin soil of Kansas. But alas, for human calculations, when Brown's party had again arrived within rifle distance, the ruffian commanders were suddenly taken with the ague; Wood, mounted the swiftest horse and left the scene of action. the other leaders and their men followed in rapid retreat.”

John Brown would continue leading the fugitive slaves over 1,100 miles during the winter to freedom in Canada. He soon left Kansas, never to return.

The Harpers Ferry Raid

In the following months, Brown continued to raise funds in the Northeast and continued working on his plan to foment a slave revolt. John Brown would receive much of his financial support from a group of six men, . Franklin B. Sanborn, Gerrit Smith, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Theodore Parker, George Luther Stearns, and Samuel Gridley Howe. These men would come to be known as the Secret Six and the Committee of Six.

In the following months, Brown continued to raise funds in the Northeast and continued working on his plan to foment a slave revolt. John Brown would receive much of his financial support from a group of six men, . Franklin B. Sanborn, Gerrit Smith, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Theodore Parker, George Luther Stearns, and Samuel Gridley Howe. These men would come to be known as the Secret Six and the Committee of Six.

He decided that he needed to bring in some professional help and hired Hugh Forbes, an English mercenary who had published a book in 1856 titled, “ Manual for the Patriotic Volunteer; On Active Service in Regular and Irregular War; Being the Art and Science of Obtaining and Maintaining Liberty and Independence”. Forbes went to Tabor, Iowa in the August of 1857 to begin drilling John Brown's recruits. When Forbes arrived, he found there were no recruits. As John Brown began to lay out his plans, for a slave revolution, there would be sharp disagreements between the two men on tactics. Furthermore Forbes would discover that Brown did not have the means to pay him what they had agreed. By November, Forbes had had enough and left to go back east.

Brown drafted a Provisional Constitution for the new state that would be formed after the slaves were freed. He took this constitution to Chatham, Ontario where there lived over 2,000 fugitive slaves. On May 8, 1858 he held a constitutional convention and the constitution was ratified. Around this time, Hugh Forbes continued to stir up trouble for John Brown by discussing Brown's planned raid with Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson. The Secret Six decided that John Brown's raid had to be postponed. Disappointed, John Brown would return to Kansas for six months and participate in helping fugitive slaves go north via the Underground Railroad.

In January 1859 after delivering a group of fugitive slaves to Canada, Brown was headed back east again. He would arrive in Harpers Ferry on July 3rd and rent a small farmhouse under the name of Isaac Smith. Although his plans called for a brigade of 4,500 men, Brown would end up with only 21 men (16 white and 5 black). Many of these men had been with John Brown in Kansas. With him were his sons, Oliver, Owen, and Watson.

In January 1859 after delivering a group of fugitive slaves to Canada, Brown was headed back east again. He would arrive in Harpers Ferry on July 3rd and rent a small farmhouse under the name of Isaac Smith. Although his plans called for a brigade of 4,500 men, Brown would end up with only 21 men (16 white and 5 black). Many of these men had been with John Brown in Kansas. With him were his sons, Oliver, Owen, and Watson.

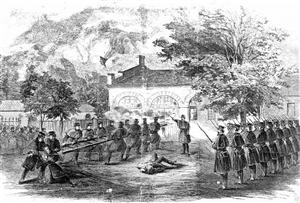

On October 16, 1859, Brown led his men in an attack on the Harpers Ferry Armory where he planned to capture arms that would be used during the slave revolt. His overall plan was to start liberating slaves in Virginia, county by county. He would then welcome freed slaves into his revolutionary army and continue moving southward until the institution of slavery had collapsed.

Initially the raid went smoothly and Brown and his men easily captured the armory. But local militia came out and surrounded the armory with Brown and his men inside. Brown had taken hostages and moved his men and the hostage into the engine house, a small brick building at the entrance to the armory.

The news of the raid reached Washington, D.C. by the morning of October 17th. The Federal government would respond by sending a company of US Marines under the command of Colonel Robert E. Lee. They in Harpers Ferry and surrounded the armory on the morning of October 18th. Lee sent Lieutenant J.E.B. Stuart forward to request the surrender of Brown and his men. Brown refused. Lee sent the marines forward and they stormed the engine house. Brown was captured along with seven of his men. Ten of the raiders were killed and five were able to escape.

The news of the raid reached Washington, D.C. by the morning of October 17th. The Federal government would respond by sending a company of US Marines under the command of Colonel Robert E. Lee. They in Harpers Ferry and surrounded the armory on the morning of October 18th. Lee sent Lieutenant J.E.B. Stuart forward to request the surrender of Brown and his men. Brown refused. Lee sent the marines forward and they stormed the engine house. Brown was captured along with seven of his men. Ten of the raiders were killed and five were able to escape.

Shortly after his capture, John Brown was interviewed by a group of Virginia citizens. John Brown made the following statement during this interview, which was published in the New York Herald on October 21, 1859:

“I have nothing to say, only that I claim to be here in carrying out a measure I believe perfectly justifiable, and not to act the part of an incendiary or ruffian, but to aid those suffering great wrong. I wish to say, furthermore, that you had better - all you people at the South - prepare yourselves for a settlement of that question that must come up for settlement sooner than you are prepared for it. The sooner you are prepared the better. You may dispose of me very easily. I am nearly disposed of now; but this question is still to be settled - this negro question I mean; the end of that is not yet. . . .”

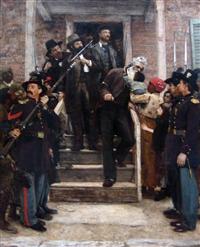

John Brown would be charged with murdering four whites and a black, with conspiring with slaves to rebel, and with treason against Virginia. He was to be tried in a Virginia court. The trial began on October 27th and the jury arrived a verdict of guilty on all counts on November 2nd. He was sentenced to hang on December 2nd.

John Brown would be charged with murdering four whites and a black, with conspiring with slaves to rebel, and with treason against Virginia. He was to be tried in a Virginia court. The trial began on October 27th and the jury arrived a verdict of guilty on all counts on November 2nd. He was sentenced to hang on December 2nd.

On the day of his death John Brown wrote:

“I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done.”

On December 2, 1859, John Brown was hanged at 11:15 a.m. and pronounced dead at 11:50 a.m. John Brown was buried at the family farm in North Elba, near present day Lake Placid, New York.

Sites of Interest

- John Brown, Jr. Grave Site, Crown Hill Cemetery

Put-in-Bay, Ottawa County, Ohio

| Waypoint = | Map |

- John Brown Farm Grounds

Off Route 73, North Elba, Essex County, New York

| Waypoint = | Map |

References

Eyewitness To History. John Brown Defends His Raid, 1859. Accessed January 10, 2010. www.eyewitnesstohistory.com .

Etcheson, Nicole. Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2006.

Gilmore, Donald L. Civil War on the Missouri-Kansas Border. Gretna: Pelican, 2006.

McGlone, Robert E. John Brown's War against Slavery. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Reynolds, David S. John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005.

Territorial Kansas Online 1854-1861. Letter, John Brown to Dear Wife [Mary Brown] & Children every one. Accessed 01/09/2010. www.territorialkansasonline.org

Wikipedia. John Brown (abolitionist). Accessed January 12, 2010. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Brown_(abolitionist)

Back: Charles Rainsford Jennison

Next: David Rice Atchison