The Oliver Anderson House

Tour Stop

Directions: The Anderson House [ Waypoint = N39 11.452 W93 52.860 ] is located on the grounds of the Battle of Lexington State Historic Site at 1101 Delaware Street, Lexington Missouri 64067.

Description: When you visit the battlefield, be sure to take the guided tour of the Anderson House-it will be well worth your time. The Anderson House was built in 1853 as a private home, during the Civil War it was used as a field hospital changing from the North to South three times. It has been beautifully restored and furnished with antiques of that period.

|

|

There was considerable controversy regarding the events that took place at the Anderson House during the battle from September 18-20th. The Federals had established the house as a hospital and were flying a white flag to mark the house as a hospital. However, Mulligan has left the house outside of his entrenchments and this greatly increased its value as a military objective. If you take the tour inside of the Anderson House, you will be able to see the effects of the fighting. There are still numerous bullet holes and holes made the the firing of cannister. Look closely at the outer brick walls on the east side of the Anderson House. Here too, is evidence of the fighting are numerous bullet holes and holes made the the firing of cannister.

|

|

An eyewitness to the battle, Susan McCausland described the importance of the Anderson House,

"The family residence of Col. Oliver Anderson stood in such proximity to the college grounds on the west that it was, from the time of the first occupancy of the college, taken into use as a hospital. The last outer entrenchments in that direction met Mrs. Anderson's flower garden, the house being so situated that the upper windows almost overlooked the interior of the works."

In his official report the commander of the Missouri State Guard, Major General Sterling Price described his understanding of the first assault on the Anderson House:

In his official report the commander of the Missouri State Guard, Major General Sterling Price described his understanding of the first assault on the Anderson House:

"Shortly after entering the city on the 18th Col. Rives, who commanded the Fourth Division in the absence of Gen. Slack, led his regiment and Col. Hughes' along the river bank to a point immediately beneath and west of the fortifications, Gen. McBride's command and a portion of Col. (Gen.) Harris' having been ordered to re-enforce him. Col. Rives, in order to cut off the enemy's means of escape, proceeded down the bank of the river to capture a steamboat which was lying just under their guns. Just at this moment a heavy fire was opened upon him from Col. Anderson's large dwelling-house on the summit of the bluffs, which the enemy were occupying as a hospital, and upon which a white flag was flying. Several companies of Gen. Harris' command and the gallant soldiers of the Fourth Division, who have won upon so many battle-fields the proud distinction of always being among the bravest of the brave, immediately rushed upon and took the place. The important position thus secured was within 125 yards of the enemy's intrenchments. A company from Col. Hughes' regiment then took possession of the boats, one of which was richly freighted with valuable stores.

"Gen. McBride's and Gen. Harris' divisions meanwhile gallantly stormed and occupied the bluffs immediately north of Anderson's house. The possession of these heights enabled our men to harass the enemy so greatly that, resolving to regain them, they made upon the house a successful assault, and one which would have been honorable to them had it not been accompanied by an act of savage barbarity--the cold-blooded and cowardly murder of three defenseless men, who had laid down their arms and surrendered themselves as prisoners.

"The position thus retaken by the enemy was soon regained by the brave men who had been driven from it, and was thence-forward held by them to the very end of the contest."

Brigadier General Thomas A. Harris, commander of the 2nd Division in the Missouri State Guard wrote of the assault in his official report:

"At 11:15 o'clock I received the order from yourself in person ... to capture the brick house outside of the enemy's line of defense, known as the Anderson house or hospital, provided, that if upon my arrival there I was of opinion I could carry it without too severe a loss. ... Upon my reaching the point known as the hospital I dismounted and ascended the hill on foot. Upon my arrival I found Col. Rives' command, supported by a portion of Lieut.-Col. Hull's and Maj. Milton's (Callaway's) command of my division. From a personal inspection of the position occupied by the hospital I became satisfied that it was invaluable to me as a point of annoyance and mask for my approach to the enemy. I at the same time received your communication as to the result of your reconnaissance through your glass. I therefore immediately ordered an assault upon the position, in which I was promptly and gallantly seconded by Col. Rives and his command. together with Col. Hull and Maj. Milton and their commands, of my own division. The hospital was promptly carried and occupied by our troops, but during the evening the enemy re-took it, and were again driven out by our men with some loss."

General Harris also reported the actions of his men at this point to prevent the Federals from re-establishing control of the river front:

"At 7:30 o'clock on the evening of the 18th instant, when a sally was anticipated from the enemy through the hospital position, designed to make a diversion favorable to the landing of anticipated Federal re-enforcements and to burn steamers captured by us during the day, you were kind enough to afford me the valuable re-enforcements from Gen. Steen's division, commanded by Majs. Thornton and Winston, and the battery of Capt. Kelley. The infantry I posted to strengthen the hospital position, and the artillery was so disposed as to command the wharf and the river. Col. Congreve Jackson politely loaned me the use of a battalion commanded by Col. Bevier, which I posted to cover the artillery. During the night I visited frequently the various positions of my command, and found both men and officers fully resolved and capable of maintaining themselves until morning."

Later during the war, Colonel James A. Mulligan gave a lecture on the Battle of Lexington which was reported in a newspaper (Colonel Mulligan's official report of the battle never reached Washington). This was his account of the fighting in and around the Anderson House:

Later during the war, Colonel James A. Mulligan gave a lecture on the Battle of Lexington which was reported in a newspaper (Colonel Mulligan's official report of the battle never reached Washington). This was his account of the fighting in and around the Anderson House:

"At noon [on September 18th] word was brought that the enemy had taken the hospital. We had not fortified that. It was situated outside the entrenchments, and I had supposed that the little white flag was a sufficient protection for the wounded and dying soldier who had finished his service and who was powerless for harm--our chaplain, our surgeon, and 150 wounded men. The enemy took it without opposition, filled it with their sharp-shooters, and from every window, from the scuttles on the roof, poured right into our entrenchments a deadly drift of lead.

"Several companies were ordered to re-take the hospital, but failed to do so. The Montgomery guard of the Irish brigade was ordered to a company which we knew would go through. Their captain admonished them that they were called upon to go where the others dared not, and they were implored to uphold the gallant name which they bore, and the word was given to "charge!" The distance across the plain from the hospital to the entrenchments was about 800 yards [actually less than 200 yards]; they started at first quick, then double quick, then on a run, then faster-still the deadly drift of lead poured upon them, but on they went--a wild line of steel, and what is better than steel, irresistible human will. They marched up to the hospital, first opened the door without shot or shout--until they encountered the enemy within, whom they hurled out and far down the hill beyond. The captain, twice wounded, came back with his brave band, through a path strewn with forty-five of the eighty lions who had gone out upon the field of death."

Years later, Union Major R.T. Van Horn recalled which of the Federal troops made the charge to retake the Anderson House from the Missouri State Guard:

Years later, Union Major R.T. Van Horn recalled which of the Federal troops made the charge to retake the Anderson House from the Missouri State Guard:

"...as I was an eye witness it must be said that there were two companies: Capt. Gleason, of the 23d Illinois, and Capt. Joseph Schmitz, of Co. B, Col. Peabody's commander, as it was called, the German company--all from St. Joseph. I was present when the two companies were drawn up to receive their orders, saw them start on a run for the hospital, saw them enter it and met them on their return. I never saw a more gallant charge or a more desperate venture. [it was a] memorable scene, and the picture of Capt. Schmitz waving his sword and charging at the head of his men is to-day as vivid in memory as it was the day I saw it enacted. ... The charge was made, and one of the most desperate, and at an enemy sheltered inside a house and using the windows as port holes."

Missouri State Guard Captain Joseph A. Wilson later recalled the fighting that took place for control of the Anderson House:

Missouri State Guard Captain Joseph A. Wilson later recalled the fighting that took place for control of the Anderson House:

"The taking of the Anderson house (hospital) by our men led to a controversy which was kept up after the war. Federals charged us with perfidy in attacking a hospital. We replied that they had fired from the building or under its cover. This they strenuously denied. At a friendly court of inquiry, sometime in the 70's, it was proven and admitted that they did fire from a point so near the building, if not actually under its cover, as to justify our men in the attack. It was also admitted that it was, at least, improper to locate the hospital at an important strategic point, just outside the works. We first took the hospital when but few armed men were in it. The Federals, in strong force, stormed and retook it. We then approached it with our rolling breast-works of hemp, captured and held it with a number of prisoners."

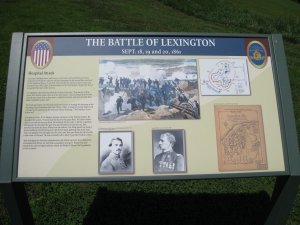

There is an interpretive sign [ Waypoint = N39 11.458 W93 52.874 ] just to the south of the Anderson House:

There is an interpretive sign [ Waypoint = N39 11.458 W93 52.874 ] just to the south of the Anderson House:

"William Oliver Anderson (1794-1873) and is son-in-law, Henry Howard Gratz, had built a prosperous business in Lexington around hemp production and rope making in the 1850's. Prior to the Civil War, Anderson became one of the most prominent residents and businessmen in the community, owner of a local newspaper and rope factory and the builder of this fine house in 1853. It was described by the Lexington Express newspaper as 'the largest and best arranged dwelling house west of St. Louis.'

"Anderson and his family lived in the house for only six years before he fell into serious financial difficulty. An Oct. 1859 public auction of his properties was held to satisfy his creditors. Thomas Akers, another son-in-law, bought the house and grounds at the auction for $7,565. He later abandoned it in the breaking storm of the Civil War.

"Anderson remained in Lexington until 1862 when he was arrested by occupying Federal troops for his Southern sympathies. He was sent to the Gratiot Prison in St. Louis and eventually paroled. He could not return to Missouri or enter any Southern state through the duration of the War. After the War he lived in Kentucky where he is buried.

"Prior to the battle, Union officers designated Anderson House as a field hospital for wounded and sick soldiers. The neutrality of such a hospital, marked by a yellow flag, would normally have been respected by both sides. However, as a result of its strategic importance and the general confusion, it was attacked repeatedly by both sides.

"The depression, to the west, is where Southern Gen. Thomas Harris 2nd Division charged the Anderson House. The house was occupied at approximately 1:00 pm on Sept. 18th. Later that day Union commander Col. James Mulligan ordered a counter assault which stormed through the back yard (see the battle damage on the back wall of the Anderson House)."

From the back of the Anderson House, walk up the hill about 0.1 miles to the east and you will find an interpretive sign [ Waypoint = N39 11.457 W93 52.736 ] entitled "Hospital Attack" that describes the fighting that took place over control of the Anderson House:

From the back of the Anderson House, walk up the hill about 0.1 miles to the east and you will find an interpretive sign [ Waypoint = N39 11.457 W93 52.736 ] entitled "Hospital Attack" that describes the fighting that took place over control of the Anderson House:

"Col. Jams Mulligan knew that his men in the outer entrenchments were easy targets for the Southern soldiers who had scampered to the second floor and roof of the Anderson House. It was from this area that the Union counter-assault was launched Sept. 18th. Eighty Federal soldiers of the Irish Brigade, charged the house, losing half their men in the process.

"Col. Mulligan afterward described the actions of his men, 'they started at first, quick, then double quick, then on a run, then faster-still, the deadly drift of lead poured upon them, but on they went-a wild line of steel, and what is better than steel, irresistible human will.'

"The Federals leaped onto the back porch and dashed in through the doorway as the defending State Guardsmen fled. One Union soldier, a musician, George Palmer, led a charge up the staircase in the Anderson House shouting, 'I will lead you if you follow me.'

"A Southern soldier, W. H. Mansur, became a prisoner of the Federal soldiers. He described the action, 'I turned and ran back to the upper floor. A Federal soldier came at me with his bayonet fixed. He evidently did not want to kill me. I grabbed the bayonet, but he jerked the gun away and threatened to bayonet me, then marched me down the stairs. When near the bottom...the firing squad was ready, I tuned suddenly, struck his bayonet with my left hand, grabbing him at the same time, and plunged over the dead into the lower hall, than ran down the hall into a side room on the east.' He was eventually led to safety by another Federal soldier.

"After dislodging the Southern sharpshooters, the Union survivors were themselves surrounded and driven out with heavy casualties. George H. Palmer was later awarded the nation's highest military award, the Medal of Honor, for his gallantry on this occasion."