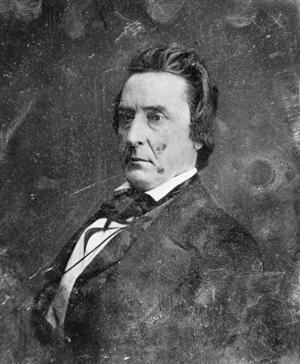

David Rice Atchison

(August 11, 1807 – January 26, 1886)

(August 11, 1807 – January 26, 1886)

David Rice Atchison was a Missouri politician who was a leader of pro-slavery supporters during Bleeding Kansas.

Pre-Civil War Role

David Rice Atchison was born in Frogtown, Kentucky (part of present day Lexington, Kentucky 40505). Atchison went to Transylvania University in Lexington and then became a lawyer in 1829. Atchison would move to Liberty, Missouri 64068 and set up a successful law practice there.

Atchison helped to organize and served as the Captain of the Liberty Blues, a company of militia. He would run for office and serve in the Missouri Legislature. Atchison was elected to the US House of Representatives in 1834. Beginning in 1835, Atchison would be a key advocate for the annexation of the Platte Territory into the state of Missouri on March 28, 1837. This extended the Missouri border to the Missouri River.

In 1841, Atchison would be appointed a judge in the 12th Judicial Circuit Court and would move to Platte City, Missouri 64079. Following his stint as a judge, David Rice Atchison would be elected to the US Senate. He was a member of the Democratic Party. He would be one of Missouri's Senators from 1843 to 1855.

U.S. Senator

When the Democrats gained control of the Senate in 1845, Atchison was chosen by the members of his party to be President pro tempore. This led to the controversial story that Atchison became “President for a Day” on Sunday, March 4, 1849 when outgoing President James Polk's term ended at noon on March 4, which was a Sunday. His successor, Zachary Taylor, refused to be sworn into office on the sabbath (Sunday). In reality, Polk's term automatically extended until President-elect Taylor was sworn in the next day.

When the Democrats gained control of the Senate in 1845, Atchison was chosen by the members of his party to be President pro tempore. This led to the controversial story that Atchison became “President for a Day” on Sunday, March 4, 1849 when outgoing President James Polk's term ended at noon on March 4, which was a Sunday. His successor, Zachary Taylor, refused to be sworn into office on the sabbath (Sunday). In reality, Polk's term automatically extended until President-elect Taylor was sworn in the next day.

It was in the 1850s that Atchison began publicly to advocate for the rights of slaveholders to take their slaves into any territory of the United States. He felt it violated their constitutional rights not to be able to take their property (i.e., slaves) with them if they chose to emigrate west. Atchison became one of the leading proponents for popular sovereignty, in which territories would vote for themselves on whether slavery would be permitted in the territory. Atchison supported the Compromise of 1850. Atchison worked closely with Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas and was instrumental in passing the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 on May 30, 1854, which repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and made popular sovereignty the law of the land.

It was in the 1850s that Atchison began publicly to advocate for the rights of slaveholders to take their slaves into any territory of the United States. He felt it violated their constitutional rights not to be able to take their property (i.e., slaves) with them if they chose to emigrate west. Atchison became one of the leading proponents for popular sovereignty, in which territories would vote for themselves on whether slavery would be permitted in the territory. Atchison supported the Compromise of 1850. Atchison worked closely with Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas and was instrumental in passing the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 on May 30, 1854, which repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and made popular sovereignty the law of the land.

From Section 1:

From Section 1:

“... said Territory or any portion of the same, shall be received into the Union with or without slavery, as their constitution may prescribe at the time of admission...”

From Section 14:

“That the Constitution, and all Laws of the United States which are not locally inapplicable, shall have the same force and effect within the said Territory of Nebraska as elsewhere within the United States, except the eighth section of the act preparatory to the admission of Missouri into the Union approved March sixth, eighteen hundred and twenty, which, being inconsistent with the principle of non-intervention by Congress with slaves in the States and Territories, as recognized by the legislation of eighteen hundred and fifty, commonly called the Compromise Measures, is hereby declared inoperative and void; it being the true intent and meaning of this act not to legislate slavery into any Territory or State, nor to exclude it therefrom, but to leave the people thereof perfectly free to form an regulate their domestic institutions in their own way, subject only to the Constitution of the United States.”

David Rice Atchison would not be re-elected by the Missouri Legislature when his term expired in 1855. But this did not stop him from taking a leadership role in the events that would follow the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854.

Bleeding Kansas

Many Missourians, particularly slave owners in the Missouri River Valley, were thrilled with the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Although bordered on the south by Arkansas, a slave state, Missouri was bordered on the north and east by states which had abolished slavery. This fear was somewhat allayed by the Fugitive Slave Act which was passed as part of the Compromise of 1850. It declared that all runaway slaves had to be returned to their owners. But Missourians feared that if the Kansas Territory voted to prohibit slavery, then Missouri would be surrounded by free states and their slaves would have better chances to escape. Missouri's leaders were committed to stopping this. Many Missourians felt they would be able to ensure that Kansas Territory would vote to make slavery legal. David Rice Atchison would play an active role in trying to make the Kansas Territory a slave state. As the Kansas Territory was opened for settlers, some Missourians began emigrating west across the Missouri River and filing claims.

But northern abolitionists had other ideas. In anticipation of the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, the Massachusetts (soon renamed to New England) Emigrant Aid Company was formed with the aim of financing the settlement of the Kansas Territory with free-state supporters. Missourians would counter by forming their own protective societies such as the Platte County Self Defense Association. Its goal was to protect the claims that pro-slavery supporters would file in the newly opened Kansas Territory. Atchison believed that the New England Emigrant Aid Company would be a real threat to his vision of Kansas as a slave state.

After the Kansas Territory was formed, President Franklin Pierce appointed its first territorial governor, Andrew H. Reeder. Reeder arrived in Kansas in October 1854. On November 29, 1854, Reeder held an election to select the territorial delegate to the US House of Representatives. Atchison went on record and encouraged Missourians to cross the border and vote in these elections. He made the following statement which was printed in the Platte Argus:

After the Kansas Territory was formed, President Franklin Pierce appointed its first territorial governor, Andrew H. Reeder. Reeder arrived in Kansas in October 1854. On November 29, 1854, Reeder held an election to select the territorial delegate to the US House of Representatives. Atchison went on record and encouraged Missourians to cross the border and vote in these elections. He made the following statement which was printed in the Platte Argus:

“When your peace, your quiet and your property depend upon your action, you can, without an exertion, send five hundred of your young men who will vote in favor of your institutions.”

Although he stayed away from any actual polling places, Atchison personally led a large number of Missourians across the border on election day to vote in the Kansas Territorial election. The pro-slavery candidate received the most votes, but many Missourians crossed the border on election day and cast ballots. Horace Greeley of the New York Tribune would give them the name, “Border Ruffians.”

Although voter fraud was widespread, few thought it had any effect on the election results. Charles Robinson, an agent of the New England Emigrant Aid Company and free-state leader, said the following about this election:

Although voter fraud was widespread, few thought it had any effect on the election results. Charles Robinson, an agent of the New England Emigrant Aid Company and free-state leader, said the following about this election:

“At this time every considerable settlement in the Territory, except Lawrence and vicinity, was pro-slavery, and an invasion was wholly unnecessary, as Whitfield could have been elected without it. Being unnecessary, it was an inexcusable blunder, as it served to expose the game the pro-slavery men proposed to play and it increased the agitation and determination of the North.”

Atchison had made a strategic error by encouraging Missourians to cross the border and vote on election day. The free-state propaganda machine went into motion and Missouri began to lose some of its support in Congress over its positions on the Kansas Territory. Ironically, Iowans also crossed the border to vote in Nebraska territorial elections, but this never received anywhere near as much bad press compared to what happened in Kansas. But Atchison would again lead Missourians across the border in March of 1855 to vote in the elections for the territorial legislature, in which 37 out of the 38 legislators elected were pro-slavery candidates. Kansas Territorial Governor Andrew Reeder overturned only the most blatant results as being fraudulent and the results were not affected. As a preventive measure, Atchison would travel to Washington to speak with President Franklin Pierce about the Kansas Territory. Later that year, Pierce would replace Reeder with Wilson Shannon as territorial governor.

Atchison had made a strategic error by encouraging Missourians to cross the border and vote on election day. The free-state propaganda machine went into motion and Missouri began to lose some of its support in Congress over its positions on the Kansas Territory. Ironically, Iowans also crossed the border to vote in Nebraska territorial elections, but this never received anywhere near as much bad press compared to what happened in Kansas. But Atchison would again lead Missourians across the border in March of 1855 to vote in the elections for the territorial legislature, in which 37 out of the 38 legislators elected were pro-slavery candidates. Kansas Territorial Governor Andrew Reeder overturned only the most blatant results as being fraudulent and the results were not affected. As a preventive measure, Atchison would travel to Washington to speak with President Franklin Pierce about the Kansas Territory. Later that year, Pierce would replace Reeder with Wilson Shannon as territorial governor.

In November of 1855, a dispute arose between Franklin M. Coleman and Jacob Branson over land claims near Hickory Point, Kansas. Eventually the dispute would result in pro-slavery Coleman shooting and killing a free-state man. In retaliation, free-state supporters burned down Coleman's house. Wyandotte County Sheriff Samuel J. Jones obtained a warrant to arrest Branson for disturbing the peace. After arresting Branson, Jones encountered a band of armed free-state supporters who demanded that Jones release Branson. Sheriff Jones requested help from Kansas Territorial Governor Wilson Shannon. Word of the difficulty of Sheriff Jones reached David Rice Atchison, who raised a large force of men in Missouri. Atchison would lead this force across the border into Kansas to support Sheriff Jones. This led to the confrontation near Lawrence, Kansas that would become known as the Wakarusa War.

In May of 1856, Atchison was directly involved in the Sacking of Lawrence leading a pro-slavery militia comprised mainly of Missourians against the free-state stronghold of Lawrence, Kansas. He directed the first cannon that fired on the Free State Hotel. Before entering into Lawrence, Atchison made a speech (reported by Joseph P. Root) to the Missourians in which he said the following:

“Gentlemen, Officers & Soldiers! - (Yells) This is the most glorious day of my life! This is the day I am a border ruffian! (Yells.) .... Now Boys, let your work be well done! (Cheers.) Faint not as you approach the city of Lawrence, but remembering your mission act with true Southern heroism, & at the word, Spring like your bloodhounds at home upon that d--d accursed abolition hole; break through every thing that may oppose your never flinching courage! - (Yells.) Yes, ruffians, draw your revolvers & bowie knives, & cool them in the heart's blood of all those d--d dogs, that dare defend that d--d breathing hole of hell. (Yells.) Tear down their boasted Free State Hotel, and if those Hellish lying free-soilers have left no port holes in it, with your unerring cannon make some, Yes, riddle it till it shall fall to the ground. Throw into the Kanzas their printing presses, & let's see if any more free speeches will be issued from them!”

Thomas H. Gladstone was an Englishman in Kansas at this time and was present in Lawrence during these events on May 21, 1856 and provided this eyewitness account:

“By this time four cannon had been brought opposite the hotel, and, under Atchison's command, they commenced to batter down the building. In this, however, they failed. The General's 'Now, boys, let her rip' was answered by some of the shot missing the mark, although the breadth of Massachusetts-street alone intervened, and the remainder of some scores of rounds leaving the walls of the hotel unharmed. They then placed kegs of gunpowder in the lower parts of the building, and attempted to blow it up. The only result was the shattering of some of the windows and other limited damage. At length, to complete the work which their own clumsiness or inebriety had rendered difficult hitherto, orders were given to fire the building, in a number of places, and, as a consequence, it was soon encircled in a mass of flames. Before evening, all that remained of the Eldridge House was a portion of one wall standing erect, and for the rest a shapeless heap of ruins.”

During the summer of 1856, an armed free-state militia began operating out of Lawrence, Kansas and dubbed Lane's Army of the North because it had been raised by James Henry Lane. There were three successive victories over the pro-slavery strongholds of Fort Franklin, Fort Saunders and Fort Titus. Territorial Governor Shannon became extremely frustrated with the unending violence and resigned as governor. In response, Atchison called for Missourians to “rally instantly to the rescue”.

During the summer of 1856, an armed free-state militia began operating out of Lawrence, Kansas and dubbed Lane's Army of the North because it had been raised by James Henry Lane. There were three successive victories over the pro-slavery strongholds of Fort Franklin, Fort Saunders and Fort Titus. Territorial Governor Shannon became extremely frustrated with the unending violence and resigned as governor. In response, Atchison called for Missourians to “rally instantly to the rescue”.

Atchison would next be seen leading a pro-slavery militia into Kansas. Part of this militia under the command of John W. Reid would split off and head for Osawatomie, Kansas, the home of Old John Brown. Once there, they would go up against John Brown during the action known as the Battle of Osawatomie. On August 30, 1856, Brown's force would be defeated and the pro-slavery militia would loot and burn the town of Osawatomie, Kansas.

Atchison would next be seen leading a pro-slavery militia into Kansas. Part of this militia under the command of John W. Reid would split off and head for Osawatomie, Kansas, the home of Old John Brown. Once there, they would go up against John Brown during the action known as the Battle of Osawatomie. On August 30, 1856, Brown's force would be defeated and the pro-slavery militia would loot and burn the town of Osawatomie, Kansas.

In September of 1856, the new Territorial Governor, John W. Geary, and immediately called for all militia to disarm and disband. Atchison returned to Missouri and an uneasy truce settled over Kansas.

In September of 1856, the new Territorial Governor, John W. Geary, and immediately called for all militia to disarm and disband. Atchison returned to Missouri and an uneasy truce settled over Kansas.

Civil War Role

In 1860 Claiborne Fox Jackson, who was pro-slavery and favored secession, was elected Governor of the State of Missouri. David Rice Atchison favored secession. He would become a political ally of Governor Jackson.

In 1860 Claiborne Fox Jackson, who was pro-slavery and favored secession, was elected Governor of the State of Missouri. David Rice Atchison favored secession. He would become a political ally of Governor Jackson.

But shortly after Jackson took office, Missouri Constitutional Convention delegates approved a resolution that stated "no adequate cause exists to impel Missouri to dissolve her connections with the Federal Union." But Jackson had other plans.

Governor Jackson began to take steps to increase the size of the state militia, which was called the Missouri State Guard. He got the state legislature to appoint Major General Sterling Price as the commander of the Missouri State Guard. Jackson also appointed David Rice Atchison as a General in the Missouri State Guard. Atchison began to actively recruit men for the guard north of the Missouri River.

Governor Jackson began to take steps to increase the size of the state militia, which was called the Missouri State Guard. He got the state legislature to appoint Major General Sterling Price as the commander of the Missouri State Guard. Jackson also appointed David Rice Atchison as a General in the Missouri State Guard. Atchison began to actively recruit men for the guard north of the Missouri River.

Atchison planned to bring the new recruits south of the Missouri River to assist Price's attack against the Union forces at Lexington, Missouri.On September 17, 1861, Atchison would lead a force of recruits against Federal troops in what would be called the Battle of Blue Mills Landing (also called the Battle of Liberty). It would be a victory for the Missouri State Guard.

Although Atchison continued to serve in the Missouri State Guard through the end of 1861, he resigned his commission following the Confederate defeat on March 8, 1862 at the Battle of Pea Ridge. He spent the remainder of the war on his farm in Plattsburg, Missouri.

Post-Civil War Role

David Rice Atchison died at the age of 78 on January 26, 1886. He was buried near his home in Greenlawn Cemetery, Plattsburg, Missouri 64477.

Sites of Interest

- David Rice Atchison Grave

Greenlawn Cemetery, 211 North Main Street, in Plattsburg, Missouri 64477

- David Rice Atchison Memorial

Clinton County Courthouse, 211 North Main Street, in Plattsburg, Missouri 64477

References

Cutler, William G. History of the State of Kansas. A.T. Andreas, 1883.

Etcheson, Nicole. Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2006.

Gilmore, Donald L. Civil War on the Missouri-Kansas Border. Gretna: Pelican, 2006.

Parrish, William E. David Rice Atchison of Missouri: Border Politician Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1961.

Back: John Brown

Next: Samuel C. Pomeroy